Our Indigenous Heroes - They Also Served

A RETURNED SOLDIERS PROTEST-THE BLACK PRINCE – written by Michael Bell – AWM – 30/5/2019

While working at the Australian War Memorial to support and promote an interest in the history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders servicemen and servicewomen, an exceptional story has come across my desk. While it contains the familiar themes of hidden heritage, and the difficulty of navigating of social norms and government policy within the young nation of Australia, the remarkable achievements of the protagonist and the questions posed by the story render it unique.

The curious epithet of "Black Prince" was given to Charles Melbourne Johnston at Gallipoli, according to the oral history passed down through two branches of the Johnston family: Rachel Hindle (née Johnston, Charles' sister), and Ian Wyllie Johnston, Charles' son, whose own nickname (bestowed on him by his uncle, the late Hon Hugh Stevenson Robertson) was "the Black".

According to Peter Wyllie Johnston, Ian referred to his father as "the Black Prince". At the time it was unclear whether the epithet was bestowed because of Charles' dark features, his strong leadership qualities and heroism on the field, or some other reason. “Uncle Ian sometimes conveyed a sense of something 'mysterious' in relation to his father's heritage, without ever explicitly stating that he believed there was Indigenous heritage in our family.”

This story has been written with the assistance of family members Andy Johnston and Peter Wyllie Johnston in the interests of furthering the knowledge and awareness of the wartime contribution of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage.

Charles Melbourne Johnston was born on 12 May 1892 in South Melbourne, the son of Adolf Charles Johnston, a Swedish-born engineer, and his wife Bertha Selvince Taglinoi Mignonneete (née Turner) from South Australia. He attended Melbourne Church of England Grammar School in 1907–1911 and at the outbreak of war in 1914 was studying law.

A group portrait of officers of the 4th Brigade Staff taken at Waterloo Camp in Belgium in March 1918. Charles Melbourne Johnston is pictured in the front row, second from left.

With his military experience as an officer with the Melbourne Grammar Volunteer School Cadets and the Citizens Military Forces, Johnston was commissioned in December 1914 as a second lieutenant. He was seconded to the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on 16 April 1915 as an officer, and embarked from Brisbane with reinforcements for the 15th Battalion that very day. After reporting for duty on Gallipoli in early June, Johnston leadership qualities were noted. On 13 September he was made temporary captain and given command of C Company to replace a wounded colleague. He remained in this role until the 15th Battalion was evacuated from Gallipoli in December 1915. In Egypt, the AIF went through a period of expansion and reorganisation. Johnston remained with the 15th Battalion, and his rank as captain was confirmed.

Captain Johnston embarked for France on 31 May 1916 and within a few months he was again promoted, this time to major, retaining command of his company. By the end of the year, Johnston had been promoted to Brigade Major of the 4th Brigade, under the command of Major General William Holmes. He retained this post until February 1918, despite being seriously wounded at Messines on 6 July 1917 when a stray shell landed in the mess tent, killing one man and seriously wounding others.

Among the “half-castes” who stood with Bennett and the 15th Battalion on Gallipoli and the Western Front was Charles Melbourne Johnston.

Later dubbed the “Black Prince”, Johnston was born in Melbourne in 1892 and educated at Melbourne Grammar.

He was studying law when the war broke in 1914 and was determined to enlist. With his experience as an officer with the Melbourne Grammar Volunteer School Cadets and the Commonwealth Military Forces, Johnston was commissioned in December 1914 as a second lieutenant and embarked from Brisbane with reinforcements for the 15th Battalion.

After reporting for duty on Gallipoli, he was made captain and given command of C Company to replace a wounded colleague.

Following the evacuation of Gallipoli, Johnston was sent to the Western Front, where he was again promoted, this time to major, retaining command of his company. By the end of the year, he had been promoted to brigade major of the 4th Brigade, retaining this post until February 1918, despite being seriously wounded at Messines in July 1917.

From February to June 1918 Johnston served with the 14th Battalion, first as commanding officer and then as second-in-command. In July, he was appointed to command the 45th Battalion, taking part in the battles of Hamel and Amiens.

He returned to the 15th Battalion in September 1918 and was in command during what he regarded as “the 15th’s last fight, and their best”, when an outpost of the Hindenburg Line was taken on 18 September. He retained his command until the 15th Battalion was disbanded in March 1919.

In recognition of his dedication and bravery, Johnston was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and was Mentioned in Dispatches three times.

Michael Bell, the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Australian War Memorial, said Johnston’s story was a remarkable one.

“His war service as an infantry officer was outstanding,” Bell said.

General Sir William Riddell Birdwood decorating an officer for bravery in the first attack on the Hindenburg Line. The ceremony took place at Ribemont.

Major Charles Melbourne Johnston DSO, 15th Battalion, stands on the far right up the back.

“He had risen through the ranks and by the age of 26 had commanded battalions in action with distinction.

“But behind all of this was the inconvenient fact that Charles Johnston, the ‘Black Prince’, was of Aboriginal heritage.”

For many years, the Aboriginal heritage of the Johnston family was known only to family members. “He’s an unusual story because he has the hidden heritage,” Bell said. “The family had long suspected their Aboriginal heritage, but it came to light through research …

“The Johnston family had retrospectively invented Spanish heritage in order to explain away their dark features and be accepted within business and social circles in Melbourne.

“When later generations asked why this deception was necessary, they received the same answer that so many before them have heard: hiding Aboriginal heritage was ‘a necessary evil’ and ‘a sign of the times’ – ‘it’s just what you did’.”

During the war, the Defence Act specifically exempted those “not of substantial European descent” from service, but many army recruiters chose to ignore the rule.

“For them, a potential soldier was a potential soldier, regardless of the colour of his skin,” Bell said.

“When recruiting guidelines in 1916 stated that ‘Aboriginals, half-castes, or men with Asiatic blood’ were not to be enlisted, this too was ignored by many.”

From 1917, the enlistment rules conceded that “half-castes” could be accepted if recruiters were satisfied that one parent was European.

“Because of the potential difficulties in enlisting, many Indigenous recruits made multiple attempts, travelling to other recruiting offices if rejected,” Bell said.

“Some tried four or five times before succeeding …In the Australian Imperial Force, everyone was paid the same, and the pay was good – six shillings a day for a private. That was comparable to a worker in Australia, and far better than the pay of British soldiers.

“As well as the allure of travel and adventure, soldiers could send money home to needy families … get out from under the yoke of the Protector of Aboriginals. “Another motive for enlisting was the warrior tradition: many enlistees were only a generation away from traditional life and took part in the tradition of protecting their Country.

“Not to mention that those who lived on mission settlements encountered the same propaganda that swelled recruiting throughout the war.”

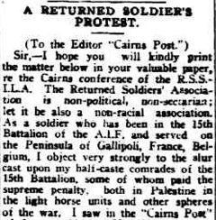

'A returned soldier's protest' published in the Cairns Post in 28 January 1933.

More than 1,000 Indigenous soldiers enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force during the First World War, and around 147 made the ultimate sacrifice.

“We now know of at least 70 Aboriginal men who served on Gallipoli, 13 of whom were killed in action,” Bell said.

“In the service, Indigenous soldiers found that they were treated as equals.

“Sadly, this changed once they returned to Australia. Out of uniform and back in their communities, they resumed being second-class citizens. Most never marched on Anzac Day, they and their families were not allowed to enter RSL clubs, they were never offered assistance from Legacy, and many had their wages stolen, while others died and were never given a proper service grave.

“James Bennett’s letter to the Cairn Post in January 1933 is significant because it is a non-Indigenous view looking at defending Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander service …

“He is writing to defend the Aboriginal people who served with him – who fought and died bravely – and his very vivid description is quite powerful.

“It protests against the denial of basic services that were denied Aboriginal people when they came back, and the right for an education and the right to get out from under the Protector, and that’s what’s significant about it; it’s a non-Indigenous man sticking up for Aboriginal people.”

A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, Bell is researching the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent and is working to identify Indigenous Australian soldiers who have served and are currently serving.

“It is important,” he said. “We’re trying to encourage people to come forward and tell their stories … to help us tell the broader story of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experience …

“Because no-one saw them, perception of their service was skewed, and for a long time it appeared as if they had never existed.”

Michael Bell, a Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Australian War Memorial. He is trying to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au