Our Indigenous Heroes - They Also Served

While we are starting to learn more about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who fought as Black Diggers during World War I, what do we know of any Indigenous sailors?

Before I start on the many Indigenous Sailors, I must tell you the history of the Victorian Naval Forces, or Colonial Forces as they were called.

In fact, the military recruitment and service of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders for their skills and knowledge of country has a long history, right from the early colonial period when British soldiers needed guides through the bush. Some Indigenous men managed to join the Australian colonial forces, such as the first recorded Aboriginal man in uniform, Thomas Bungalene, who enlisted in the Victorian Colonial Navy in 1861 – though Thomas seems to have been sent to the navy to ‘benefit from the discipline’.

It has previously been assumed that the Victorian Navy consisted of men of European descent. Part of the problem in identifying ethnicity is that non-European men were not described in terms of their ethnic background.

Unlike Asian names, the names of men of Australian Aboriginal and African descent do not necessarily identify their ethnicity. Likewise, Certificates of Service and Enrolment Sheets for the men of the Permanent Force do not describe the individual's ethnicity. However, the Victorian Naval Reserve register does list the eye colour and complexion of some of the men. Harry Moore (aka Black Harry), who was described in the press as "a coloured man" ( A Jamaican) and of whom we have photographs, was listed as having a dark complexion and dark eyes. Apparently, this description was also applied to Australian Aboriginal servicemen in the First World War.

From the first intake in 1860, men described by themselves as "Sandridge darkeys" were sworn in as members of the Sandridge Naval Brigade. Non-European men served in both divisions of the Naval Reserve/Brigade and the Permanent Victorian Navy. It would appear that the Victorian Naval Forces were more multicultural than has previously been assumed.

While recent focus on Black Diggers during World War I has shown hundreds served – often unrecognised and who continued to be unrewarded long after the war – it appears there are no historical records of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander service in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) at this time.

Considering that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders had a long tradition of working in maritime industries – from fishing in the early colony of New South Wales to voyagers such as Bungaree and his circumnavigation of the continent with Matthew Flinders in 1803, to whaling in the southern oceans and pearling in the north and west – it would be surprising if some Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders had not served in the navy before the sailors on HMAS Geranium in 1926.

The RAN differed from the Australian infantry in that it was a small, professional service established before the war. It didn’t need the tens of thousands of volunteers that the army was to require. After Federation in 1901, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men were not citizens and therefore could not join the armed forces. While some hid their identity and managed to join up, and others were overlooked when recruitment became more desperate, it would have been very difficult for such men to join the small naval service, which comprised just two to five thousand personnel throughout the war.

But with the RAN’s history of temporarily recruiting non-Australians, and the long history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people willing to serve their country despite Australian racism and lack of recognition of their service, the question arises whether there were any Black Sailors who served along with the Black Diggers in WWI?

Victoria was separated from the mother colony of New South Wales in 1851, and was quick to realise that her very existence could stand in jeopardy without a navy. Gold discoveries drew thousands of people from all over the world to Victoria by mid-1852. There was no way for local authorities to enforce control over the port waters, so an appeal was made to the Imperial Government for an armed vessel to be stationed in Port Phillip. HMS Electr, under Captain Morris, arrived at Williamstown in April 1853.

Electra was inadequate, and Sir Charles Hotham applied for a vessel similar to HMS Devastation to be sent out at Imperial Government expense. This request was not complied with, so Victoria ordered a screw sloop of war from the Limehouse yard of Young Son & Magnay. The first war vessel built to the order of any British colony, which cost $76,000, was of 580 tons and had a speed of 13 knots. Commander William Norman brought her out and anchored her off the site of the dockyard on 31st May 1856.

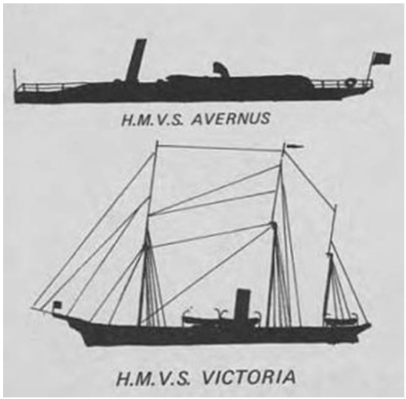

Principal employment of HMCS Victoria was rendering assistance to shipwrecked mariners, carrying out coastal surveys, storing lighthouses, and serving as a water police ship. She repatriated stranded diggers from the abortive Port Curtis goldrush in 1858 and searched Northern Australian waters for Burke and Wills in 1861. (Thomas Bungalene was on this voyage). Her declining years were spent as a general-purpose hack, and she was broken up at Williamstown in 1896.

Victoria went to war once, when she operated as a dispatch vessel attached to HMS Pelorus in New Zealand waters during the Taranaki Rebellion. She landed a party of her seamen who constructed a redoubt under heavy fire. Her armament at the time comprised a 32 pivot gun forward and aft, two similar long guns broadside, and four short 32s.

War in the Crimea caused local panic with fears of invasion by a cruising Russian squadron. In anticipation of a war, fortifications were set up as a massive semicircular redoubt enclosing a portion of the land now occupied by the dockyard. These works, completed in 1855, were demolished six years later. The parapet was seven feet high, eighteen feet wide at the summit, and twenty-six feet at the base. Chief Harbour Master, Captain Charles Ferguson, raised an artillery force to man the defences, and on 8th April 1856, this became the Williamstown Division of the Victoria Marine Artillery Corps. Williamstown and Port Melbourne were charged with the task of raising the Victoria Naval Brigade in 1859. Manning guns of the port blockship Sir Harry Smith was their first task.

The Colonial Naval Defence Act of 1865 laid down a definite policy by which colonies could provide, maintain, and use their own vessels of war. Permanent naval forces could be raised and volunteers enlisted for the Royal Naval Reserve. After the implementation of the Act, vessels of the Victorian Navy were titled HM Victorian Ships instead of HM Colonial Ships, although official correspondence shows occasional lapses until the hoisting of the Victoria Ensign.

George Verdon (later Sir) was sent to consult the Imperial Government on naval defence matters for Victoria in 1866. Verdon represented Williamstown in Parliament. He obtained from the British Government the old wooden battleship Nelson for use as a naval training ship, and $200,000 towards the cost of the ironclad turret ship Cerberus. Nelson was laid down in 1805 as the first ship of the line built in England after the Battle of Trafalgar.

She was launched in 1814, too late to take part in the Napoleonic Wars, and as peace brought the usual drastic reduction in naval forces, the vessel spent most of her life laid up, until she was cut down to a two-decker and fitted with an auxiliary steam engine and screw. Originally, she carried 126 guns and a crew of 875. She was reduced to a single-decker at Williamstown Dockyard in 1881.

Captain Charles Payne went to England with Verdon and brought back Nelson. He remained in charge of the vessel until the death of Captain Ferguson in 1870, when he was appointed Chief Harbour Master. Nelson became a training ship for ‘... waifs and strays who had become a burden on the colony either by death of parents or desertion of them . . .’ soon after she made port in February 1868. The average annual number borne on her books was 350 boys, controlled by 36 officers and men.

Nelson was used for a time as a store ship lying off Fishermen’s Bend. She was sold at auction by the British Government in 1898 to Mr. B. Einerson of Sydney for $4,800. She became a Union Steamship Co. coal hulk at Sydney in 1901. She was towed to Beauty Point on the Tamar in 1908 and later to Hobart, where she went to the breakers in 1924. The remains were fired at Shag Bay to secure some tons of gunmetal and bronze fastenings.

The national flag granted to the Colony of Victoria was officially inaugurated in 1870 when it was broken out on the mainmast of HMVS Nelson. It incorporated the Union Flag in the upper left quadrant and the Southern Cross on an azure field. The new mercantile Red Ensign was flown from the mizzen.

Naval brigade gun teams exercised in Nelson for the first time on 10th September 1870. They were unpopular on the eastern shore of the bay in 1877, when they loosed a projectile which landed at the railway station entrance, narrowly missing killing a Chinese.

Nelson took part in a mock attack on Williamstown batteries in 1876. All arms of the services took part in the exercise, and there were about 2,000 to 3,000 troops deployed around the Bay. Nelson landed a task force of the Naval Reserve below Brighton and proceeded to attack the Williamstown batteries, which were declared destroyed because their guns could not be brought to bear on the vessel. Nelson at this time carried two 116-pdrs., twenty 64-pdrs., 20 smooth bore 32-pdrs. and six 12 pdrs.

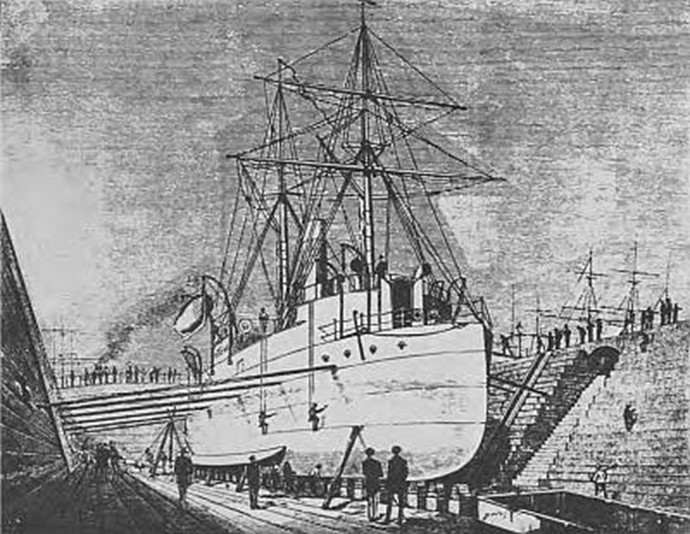

Gun-boat VICTORIA in the Government Graving Dock at Williamstown.

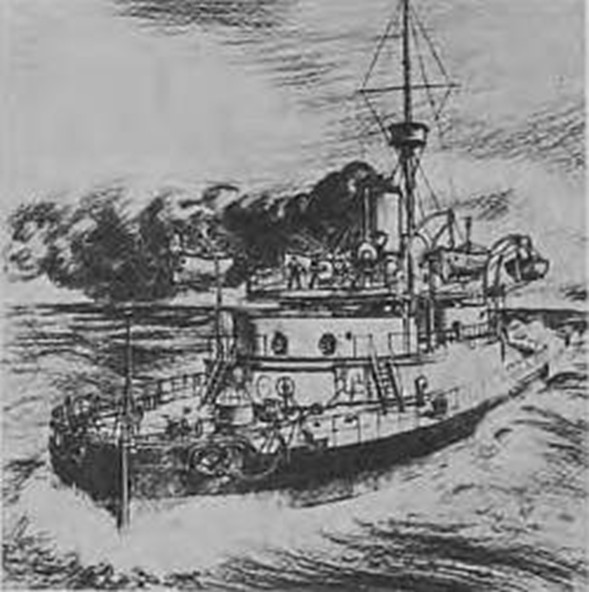

HMVS Cerberus, laid down at Palmers yard on 1st September 1867, was launched on 2nd December 1868. Completed in September 1870, she sailed from Plymouth on 8th November. As her maximum coal capacity of 210 tons was inadequate for the voyage out to Melbourne, temporary sides were built up to the breastwork, and she was given a full three-masted rig. She arrived at Williamstown on 9th April 1871 after a passage largely under sail.

Cerberus displaced 3,340 tons. With a length of 225 feet, her hull had a freeboard of only 3½ feet, with a central armoured breastwork amidships rising 7 feet above the deck. She carried four 18-ton 10-inch Woolwich muzzle-loading rifled guns in her two turrets, with several Gatling machine guns mounted on the superstructure. She had her square-box pattern boilers removed in 1883 and replaced by cylindrical boilers, which gave her a top speed of 9 knots, or a knot less than her original speed.

Cerberus was used as an explosives store ship for about 30 years until 1921, when she was towed to Geelong for use as a depot ship for the newly formed submarine base. She was rechristened Platypus II. She was later sold for little more than forty pounds and towed from Corio Bay to Williamstown Dockyard on 14th May 1924 for dismantling. She was purchased from the Melbourne Salvage Company by the Brighton Yacht Club and used to form a breakwater at Black Rock.

Victorian Naval expenditure in 1865 was £7,743, which rose to £17,135 by 1875. This did not allow for the £73,520 towards the cost of Cerberus and £28,520 for Nelson. The naval strength was then 20 officers, 284 petty officers and seamen, and 40 boy seamen. Naval Reserve strength mustered aboard Nelson for shot and shell practice in 1883 was 216 officers and men.

The next year, the first class torpedo boat Childers joined the fleet, armed with four torpedoes for releasing over the side by dropping gear, and two Hotchkiss guns. The same year, the steam hoppers Batman and Fawkner of the Melbourne Harbour Trust were added to the fleet as auxiliaries. Batman mounted a 14-ton gun and two Nordenfelts, while Fawkner was fitted with a 4-ton gun and two Gatlings.

The fleet in 1889 consisted of Nelson, Cerberus, Batman, Fawkner, Childers, Nepean, Lonsdale, Victoria, Albert, Gordon, Commissioner, Lion, Gannet and Lady Loch. Nepean and Lonsdale were second-class torpedo boats, each armed with two Whitehead and two spar torpedoes. The gunboat Albert was of 350 tons displacement with 400 IHP engines driving her at 10 knots. She was built of steel with a turtle deck and a bridge deck amidships enclosing the engines. She was armed with a 12.5-ton 8-inch gun forward and a 4.5-ton breechloader aft. She also mounted two 9 pdrs. and two Nordenfelt machine guns.

The larger vessel, Victoria, was 530 tons and mounted one 10-inch gun, two 12 pdrs. and two Nordenfelts. Both gunboats were meant for harbour defence and behaved very badly in rough weather, or indeed, with any sea running at all. Victoria was sold to the West Australian Government in 1896.

The Customs steam launch Lion and the Harbour Trust launch Commissioner, when operating with the Victoria Navy, each carried two Whitehead torpedoes. The Harbour Trust tug Gannet mounted a 14-ton gun and two Gatlings. Lady Loch was built for the Department of Trade and Customs, and as a Victorian Navy vessel, mounted a 4-ton gun and two Nordenfelts.

Gordon was a turnabout torpedo launch armed with two Whitehead torpedoes and a Nordenfelt. There was also Pharos, a composite auxiliary screw steamer built at Williamstown in 1865. She was brigantine rigged and built for survey purposes, but was found to be totally unsuitable, and the old Colonial Victoria was recommissioned from reserve. Pharos was chiefly used for laying buoys and carrying stores to lighthouses and telegraph stations. She was sold out of Government service and was used as a tug and excursion steamer before finishing her life as a hulk. The Government tugs Bendigo and George Rennie, both sidewheel paddle steamers, also operated with the Victorian Navy for varying periods.

The last vessel built for the Colony of Victoria was the first-class torpedo boat Countess of Hopetoun.

She was built at the yard of Yarrow and Co. on the Thames, and as the contract called for delivery at Williamstown, she was sailed out rigged as a three-masted schooner. The voyage lasted 154 days. Her displacement was 75 tons, and her dimensions were 130 feet by 13 feet 6 inches beam. She had a 6-inch torpedo tube built into her counter and two 14-inch tubes on a revolving platform aft. Three heavy machine guns were mounted for protection. Her original speed exceeded 24 knots, but when she was slipped in August 1892, an accident on the cradle buckled her keel and retarded her top speed. She was christened in the Alfred Graving Dock by Lady Hopetoun, wife of the Governor of Victoria. The dock was flooded, and Lady Hopetoun pressed a switch that fired a torpedo to shatter a bottle of champagne suspended over the mouth of the forward torpedo tube.

Rear Admiral George Tryon conferred with the Premiers of the Australian Colonies on questions of naval defence, and as a result, a Colonial Conference was held at London in 1887. This resulted, among other things, in the passing of the Australasian Naval Defence Act.

It was decided to supplement the Australian Station with an auxiliary squadron. The Colonies concerned paid 5 per cent of the initial cost and $182,000 annually towards maintenance. The squadron in 1891 comprised the five third-class cruisers Katoomba (flagship), Mildura, Ringarooma, Tauranga and Wallaroo and the two torpedo gunboats Boomerang and Karrakatta. Three cruisers and one gunboat were to be kept in commission, and the remainder in reserve at Australian ports.

The Auxiliary Squadron visited Williamstown in 1891 and was made very welcome. The vessels were Tauranga. Ringarooma, Wallaroo, Boomerang and Karrakatta. The permanent Victoria Naval Forces in 1895 numbered 175 officers and men. They were divided up, while Cerberus and the torpedo boats were in port, between Cerberus, Nelson and the Dockyard or Torpedo Depot. The Government ordered the disbandment of the Naval Brigade in 1895. This did not become effective until 30th June 1904.

In 1900, a force from the Victorian Naval Brigade was raised to take part in quenching the Boxer Rebellion. Three times the required number of volunteers was obtained, and a selection had to be made. The force, under Captain Tickell, sailed in the steamship Salamis in September 1900 and saw service until March of the next year. The sailors disembarked at Taku and moved up the Pei-Ho River to Tientsin by lighter. They took part in putting Cheng-Ting Fu to the torch and in the attack on the Pei-Tang fort, arrived too late and were just in time to see it fall to the Austrian troops. The only other action they saw was during abortive affrays about Tientsin.

Naval Commandants of NSW, Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania and the Secretary of the Victorian Defence Department prepared a report in 1899, which laid the foundations for a single united Australian fleet. State Naval forces were transferred to the Commonwealth in March 1901, and were administered under State Acts and regulations until the Commonwealth Defence Act 1903 came into force on 1st March 1904.

Moving forward to post-WWI. Not sure if any Aboriginal sailors actually served in WWI, we do know that there was a crew of 19 aboard HMAS Geranium called ‘The Black Watch’.

These Aboriginal Sailors worked on Geranium when she was conducting a mapping survey of waters across the north and west of Australia in 1926. HMAS Geranium was launched on 8 November 1915 and commissioned on 6 March 1916 under the command of Lieutenant Commander James Forest Dewar, RN.

Geranium served as a minesweeper and convoy escort in the Mediterranean during 1916-1919.

On 17 January 1920, Geranium was re-activated, under the command of Lieutenant Arthur Smith, RN, in preparation for minesweeping training duties. She was commissioned as HMAS Geranium on 14 February 1920 under the command of Lieutenant Frederick Arthur Pearce, RN and operated briefly in Tasmanian waters in March. She returned to Sydney on 22 March and was alongside for the next two months. Lieutenant Commander William Mervyn Vaughan-Lewis, RN, took command of Geranium on 27 April 1920, and the vessel supported Admiral Jellicoe’s visit to Australia during May-June 1920. She was decommissioned at Sydney on 30 June 1920.

Prior to 1920, the charting of Australia’s coastal waters had been the responsibility of the Royal Navy. Following the end of the war, this responsibility was transferred to the RAN and the Australian Hydrographic Service was formed on 1 October 1920. The Royal Navy agreed to assist with survey work until the RAN could take over full responsibility, and HMS Fantome operated in Australian waters during 1920-23 and HMS Herald during 1924-26.

HMAS Geranium was commissioned as a survey vessel on 1 July 1920 at Sydney, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Vaughan-Lewis. Her ship's company as a minesweeper was 77, but as a survey vessel it increased to 113 personnel, including up to six seaman officers, an engineer lieutenant, a surgeon lieutenant and a paymaster officer. The ship's minesweeper design made it suitable for handling survey equipment, but she was to prove to be less than suitable for surveying duties in tropical Australian waters, as she had been designed for operations in the northern hemisphere.

The ship’s first survey task was to conduct a reconnaissance of Napier Broome Bay on the north-west coast of Western Australia. She sailed from Sydney on 17 August 1920, steaming via Townsville, Cairns and Darwin to arrive at Napier Broome Bay in mid-September to conduct a survey of the area for its use as a naval anchorage.

HMAS Geranium after recommissioning in 1920.

On 26 September 1920, a survey party was landed at Napier Broome Bay and during the day, Warrant Officer (Gunner) John Henry Davies went missing. A search was conducted over the next five days, including the use of Aboriginal trackers from a nearby mission station, but no sign of the unfortunate officer was found. Some weeks later, Gunner Davies’ badly mauled body was located in mangroves some distance from the bay. His remains were buried at Pago Mission Cemetery, and his death was attributed to being killed by a crocodile.

In 1923, after spending time between the North-Northwest Coast and the East Coast of Australia, she returned to Darwin. During this visit to Darwin, six Aboriginals from Bathurst Island embarked to undertake additional labouring duties. These men wore a naval uniform, with a cap bearing an HMAS Geranium tally band, and were paid a daily wage that was the equivalent of the cost of a glass of beer, while the senior Aboriginal was paid a daily wage equivalent to a glass of whiskey. While they wore naval uniform and were paid, they were not enlisted in the RAN.

They also slept on the upper deck in an area separate from the ship’s company. It was commonplace in the Royal Navy to take on board local labour in Asia, India and Africa for mundane work such as cleaning, but it was rare for the RAN, especially in Australian waters. Some of Geranium’s sailors were less than happy to have these men on board and made their displeasure well known.

Geranium departed Darwin on 15 June and returned to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Not long after arriving back in the survey area, a group of officers, while visiting one of the small islands, found an ochre-painted log that had been hollowed out and contained the remains of a long-deceased Aboriginal. The log had originally been plugged with clay at each end. Surgeon Lieutenant William Edward Paradice, RAN, a noted collector of marine animals and insects for the Australian Museum, thought the item would make an excellent addition to the museum and decided to bring it back on board the ship.

When this log coffin was brought on board, the Aboriginal sailors went into immediate panic, calling out that the log "contained a devil" and that it should be taken ashore immediately or bad luck would befall the ship. The log coffin remained on board, and the Aboriginal sailors refused to go near where it was stored; this only added to the morose feelings of those on board.

On 27 June, the ship was operating near Vanderlin Island. That afternoon, Commander Bennett decided to anchor the ship for the night. Able Seaman Alick 'Chook’ Fowler recalled the events that followed - “The skipper told the bridge personnel that the ship would go to anchor. At about 1530, I asked the skipper if he required the sounding recorder, and he said, “No, Fowler, we’ve been in this area before”. I was the sounding recorder, and I could not remember being there before, but then who was to have a better memory than an officer?

The Captain then told me, “Go aft and tell No.1 (the First Lieutenant) we will be anchoring in five minutes”. So I left the bridge and made my way along the boat deck and down the ladder to the quarterdeck and found the First Lieutenant (Lieutenant Dixon). Just as I said, “Sir, compliments of the Captain, we are going to anchor in five minutes”, we hit a reef.

The ship rolled to starboard, then to port, straightened up with her snout up in the air and her stern partly submerged. The First Lieutenant then said to me, “Fowler, I think we are bloody well and truly anchored now”. Well, after that, it was all hands to the pumps, and whatever could be spared had to be moved aft. All the heavy gear from the mining room amidships below the mess-deck was manhandled off the ship into its boats.”

Geranium had struck an uncharted reef and was in serious trouble. Bennett put out two of the ship’s anchors astern of the stricken vessel - these had to be taken out by the ship’s boats and dropped overboard by hand. Her engines were then put to full astern to pull Geranium off the reef. One of the anchor cables parted under the strain, but the other held. The ship’s company were also mustered aft to ‘whip-jump’ the ship (jump and down to set up a resonance that could help shake the ship free of the reef).

At around midnight, Geranium finally slid off the reef but then began to settle by the bow. Engineer Lieutenant George Arnold Hutchison (who had served in the Navy since 1910 and had been on board HMAS Sydney when she had sunk the Emden in 1914) took charge of the damage control efforts. Trees from nearby islands were cut down for use as shoring, while the pumps were used to remove the ingress of water. The ship was then moved to a nearby bay and settled onto the mud flat at low tide, for repairs to continue. A collision mat and coal bags, filled with cement, were used to pack the damaged hull areas.

She was re-floated the next day at high tide, but her keel was badly buckled and holed in places. On 1 July, the Royal Navy survey vessel HMS Fantome, also operating in northern Australian waters, supplied an extra collision mat and cement to plug the leaks and escorted the ship to Thursday Island.

It was here that the Aboriginal coffin was taken ashore, but the ship’s bad luck was not yet over as the cutter conveying the coffin collided with a pearling lugger en route. The six Aboriginal labourers were also put ashore at Thursday Island as they could not be taken to Sydney. The reef that Geranium struck (south of Wheatley Islet) was subsequently named Disaster Reef, and the bay she stopped at for repairs was named Geranium Bay.

Our Indigenous Heroes Team

Sources:

Indigenous Histories-Philippa Scarlett

RAN History