Our Indigenous Heroes - They Also Served

Bungaree must go down in history as one of the most influential Aboriginal men who paved the way in communication between the British and the traditional landowners.

Some believe that he did not voluntarily join the HMS Investigator but was encouraged to come along for the journey.

Who knows what was correct, however, let me tell you about Bungaree or the ‘King of Broken Bay’ as he was known. He has been documented as the first Aboriginal man to sail with the British.

BUNGAREE

Bungaree, or Boongaree (c. 1775 – 24 November 1830), born presumably in the Rocky Point area, New South Wales, was an Aboriginal Australian from the Darug people of the Broken Bay north of Sydney, who was known as an explorer, entertainer, and Aboriginal community leader.

Bungaree is a remarkable and enigmatic figure in Sydney and Australia’s colonial history. He is notable as the first Aboriginal Australian, and indeed the first Australian-born person, to circumnavigate the continent as a crewman on the Investigator with English explorer Matthew Flinders during their voyages of 1802–03. Flinders recruited Bungaree for that historically significant voyage primarily to act as an intermediary with the Indigenous people they were to encounter.

Originally from Garigal country, near present-day Broken Bay just north of Sydney, Bungaree was recognised as a leader among his own people. Bungaree’s intelligence and adaptability were evidenced in how quickly he learned to speak English and the use he made of it to speak directly with the growing colony and its key players.

He became very familiar with white colonists in the newly established settlement at Warrane (Sydney/Port Jackson). He sold or bartered fish with the colonists and occasionally sold Aboriginal weapons to collectors from passing ships, spending his life in the widening gulf between the world he grew up in and the hostile new world of the Sydney colony.

When Bungaree moved to the growing settlement of Sydney in the 1790s, he established himself as a well-known identity able to move between his own people and the newcomers. Bungaree and Flinders first met in 1798 onboard the HMS Reliance on a trip to Norfolk Island 1798, during which he impressed Matthew Flinders. In 1798, he accompanied Flinders (and his brother, Samuel Ward Flinders, a midshipman from the Reliance) on a coastal survey in the sloop Norfolk as an interpreter, guide and negotiator with local indigenous groups.

They were then both young men aged in their twenties. As a crew member on the Reliance, this was the first recorded instance of Bungaree as a sailor, employed alongside his countrymen Nanbarry and Wangal.

The following year Flinders recruited Bungaree on the first coastal survey of Bribie Island and Hervey Bay in present-day Queensland. Flinders later wrote of Bungaree... ‘of good disposition and open and manly conduct had attracted my esteem’ and remarked on Bungaree’s kindness toward Flinders’ cat Trim, who had accompanied Flinders on the Investigator.

Bungaree was recruited by Flinders to accompany him on his circumnavigation of Australia in Investigator, between 1801 and 1803. Flinders was the cartographer of the first complete map of Australia, filling in the gaps left by previous cartographic expeditions, and was the most prominent advocate for naming the continent "Australia".

Flinders noted that Bungaree was "a worthy and brave fellow" who, on a number of occasions, saved the expedition. Bungaree was the only indigenous Australian on the ship and, as such, played a vital diplomatic role as the expedition made its way around the coast, overcoming considerable language barriers in places.

According to historian Keith Vincent, Bungaree chose the role as a go-between and was often able to mollify indigenous people who were about to attack the sailors by taking off his clothes and speaking to people, despite being in territory unknown to him.

In 1815, Governor Lachlan Macquarie dubbed Bungaree "Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe" and presented him with 15 acres (61,000 m2) of land on George's Head on the harbour’s north shore, where Bungaree stayed for a short time with his extended family.

Georges Head was a good vantage point for sighting the arrival of ships into Sydney Harbour. Bungaree would greet incoming vessels in his small fishing boat, asking newcomers for the ‘tribute’ he said was owed to him. Artist Augustus Earle, in his Views in New South Wales and Van Diemens Land (London, 1830), recalls him welcoming Europeans to ‘his country’. This is perhaps the first recorded use of the term Country by an Aboriginal person to reference their lands, waters and ancestral connections.

He also gave him a breastplate inscribed "BOONGAREE – Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe – 1815". Bungaree was also known by the titles "King of Port Jackson" and "King of the Blacks", with his principal wife, Cora Gooseberry, known as his queen.

Bungaree also later sailed with Lieutenant Phillip Parker King on the Mermaid in 1817, exploring the north-west coast of Australia before visiting the island of Timor, returning to Sydney in 1818.

Bungaree became acquainted with several prominent colonists and governors. Amongst other things, giving advice on which plants were safe to eat.

Bungaree spent the rest of his life ceremonially welcoming visitors to Australia, educating people about Aboriginal culture (especially boomerang throwing), and soliciting tribute, especially from ships visiting Sydney. He was also influential within his own community, taking part in corroborees, trading in fish, and helping to keep the peace.

In 1828, he and his clan moved to the Governor's Domain and were given rations, with Bungaree described as 'in the last stages of human infirmity'. He died at Garden Island on 24 November 1830 and was buried in Rose Bay. Obituaries of him were carried in the Sydney Gazette and The Australian.

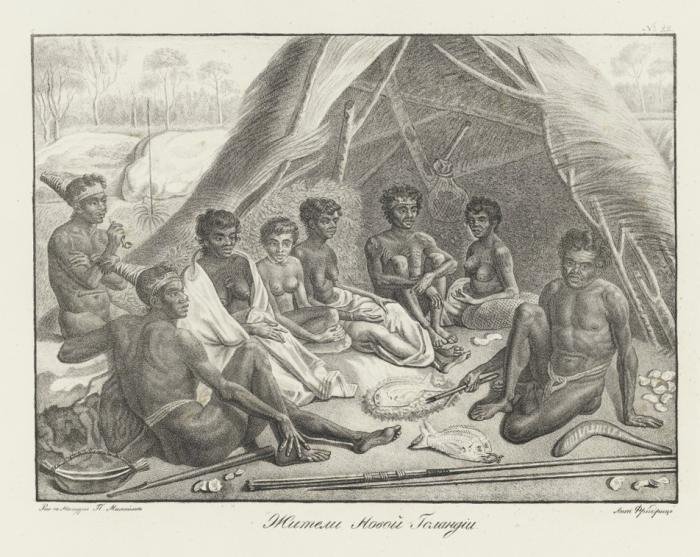

By the end of his life, he had become a familiar sight in colonial Sydney, dressed in a succession of military and naval uniforms that had been given to him. His distinctive outfits and notoriety within colonial society, as well as his gift for humour and mimicry, especially his impressions of past and present governors, made him a popular subject for portrait painters, with eighteen portraits and half a dozen incidental appearances in wider landscapes or groupings of figures. His works were among the first full-length oil portraits to be painted in the colony, and the first to be published as a lithograph.

Aboriginal society, however, had no concept of hereditary entitlement, placing greater stead in a leader’s age and experience. These breastplates were ostensibly used to elevate or recognise the status of Aboriginal leaders, but this system was simply another attempt to replace Aboriginal leadership, law and governance with a more ‘acceptable’ context and terminology. Later, breastplates would often replace the word Chief with King or Queen, terms which do not begin to capture the complexities and nuances of Aboriginal governance and authority.

As a leading statesman and eloquent speaker, Bungaree fascinated colonial authorities, writers and artists, who often referenced his breastplate. This was perhaps to elevate his status and indicate his acceptance within Sydney’s increasingly white population.

In his final years, Bungaree lived with his family on the Governor’s Domain (the Domain). He was an easily recognised character and somewhat the joker, entertaining Sydneysiders with his flamboyant impressions of former governors in exchange for grog or tobacco. Portraits held by the Library show him depicted by colonial artists dressed mostly in military or naval uniforms with a cocked hat and wearing his breastplate.

Bungaree was admitted to the General Hospital in 1830, aged in his 50s and affected by alcohol and malnutrition. Anxious to return to his people, he was soon given rations and released. Bungaree died at Garden Island in November 1830 and was buried by his people at Rose Bay alongside his first wife, Matora. The breastplate given to him by Governor Macquarie was buried with him. An obituary for Bungaree appeared in the Sydney Gazette. He was survived by another wife, Karoo, known as Cora Gooseberry, who was also well-known on the streets of Sydney. A memorial plaque honouring Bungaree was erected at Rose Bay in 2016.

Seventeen artists’ portraits were created depicting Bungaree. Many of these portraits were posthumous, published in the 1830s and 1840s. Bungaree became a kind of celebrity figure, even after his passing. He was the person urban Europeans conjured into their imaginations when they were thinking of prominent local Aboriginal people, long past his death, possibly because of the contradictions of being a ‘king’ who did not conform. Bungaree was the most commonly depicted figure in the colony and appeared in many sketches and illustrations, cementing his iconic status for many colonists and visiting strangers.

A sculpture of him, by Aboriginal sculptor Laurie Nilson, can be seen in Mosman Town Hall. It is perhaps telling that despite the fame and affection Bungaree was sometimes afforded, he was not publicly honoured in the same way as white male figures from the same period, and his notable absence from Macquarie Street’s parade of statues remains a point of contention and conversation. For many, the fact that Flinders and his cat have prominent statues is particularly galling, given Bungaree’s pivotal role, but it is worth considering that perhaps a colonial-style statue alongside Flinders is not the best way to honour this incredible man. Being permanently associated with Flinders as part of his honorary tableau does little to honour Bungaree’s life and reinforces the old-fashioned idea that his accomplishments were merely extensions of colonial glory.

Sydney Stock and Station Journal (NSW: 1896 - 1924), Tuesday 16 May 1899, page 8

When Bungaree was King.

BY 'BOOMERANG.'

'Awake my muse! thyself infuse. The past to us to bring, To tell the ways of other days When Bungaree was king.'

Yes sir, that sable monarch was the last king of any moment, after the white man with his evangelizing influences of rum and tobacco, taught the children of the boomerang and spear the ways of Christian civilisation; and it must be admitted that they have been thinned out, as at a rough guess, there were in those days something like 100,000 blacks in New South Wales alone. Now in about 100 years — say from Goulburn to Sydney — they have been held very low in the scale of humanity. Too much so, I fancy, to be true. For as mimics they were unrivalled. Again, in throwing and tracking and in all other things displaying the gifts of sight, hearing, and quick observation of external nature they were unsurpassed.

Well, his sable majesty (Bungaree) had two queens — one, I think, called Gooseberry, and the other Sugarbag. They were of inestimable use to their dusky lord, in giving him full leisure to ponder on approaching changes. This was abundantly manifested when the royal party went on a fishing excursion — for his majesty had a boat given to him, and he might have been seen on many occasions lounging smoking in his vessel while his two wives pulled the oars and caught the fish. He always said he 'lubbed' that one best that caught most 'fis.' Nor should his 'make-up' be for-gotten. It consisted of an old cocked hat and coat that were once the property of an admiral; and as the weather was generally mild, these constituted the whole of his toilet.

Now, it must not be supposed that he was without any desire to notice the peculiarities of his betters. In the time of Sir Thomas Brisbane, who was given to the study of astronomy, and could often be seen pointing his telescope heavenwards in quest of the deep mysteries there involved, Bungaree, to be quite up to the thing, got a hollow stick, and often, both day and night, might be noticed putting one end of the mimic telescope to his eye in perfect imitation of the Governor. When Sir George Gipps arrived Bungaree studied him and soon copied to the life the new Governor's quick, short mode of address.

So many of his old chums had to put up with, 'Oh, oh; how do? how do?' and, shaking his hand very quickly, 'Very busy, very busy — can't stop to talk' instead of the lounging game of a few weeks before. Bungaree, in Macquarie's time, visited Government House, and dined there a few times, until his voracity in relation to rice puddings made it desirable to give his majesty a stipulated portion out-side on the grass. By the way, it was not long since that Prince Timothy, eldest son of King Thackambau, of Fiji, did something of the same.

But, to return to the other: Bungaree was a mild and peaceful man, wanting only food, tobacco and rum. The tribal feuds, which were always quickly settled, were generally over a woman. For that kind of bird, from the time of Ellen of Troy, all grades of men, from kings to blackfellows, have been moved to heroics and absurd actions; and even Virgil states that the mild eyes of a heifer will wax with interest two fierce and strong bulls to goring each other to death to obtain a little of her gentle love. Then, what are we to say to Darwin? or what to Pope? who has written — 'We are but parts of one stupendous whole, Whose body nature is and God the soul?'

Bungaree, I may state, was King of the Port Jackson tribe, which, perhaps extended round Botany, to Cook's River and half way to Parramatta, or as I believe it should be 'Barramatta,' which means, in the native dialect, the place where eels are, for the salt-water eels used to go up as far as where the dam is now, to meet the fresh water stream, where it met the tide waters of the river, in search of anything that might come down.

And the sable ruler, or king was Bimble Woy, a rum and tobacco disciple, of course. But while on my black countrymen, I will take my listeners back to the days of Governor Phillip, whose grave has so lately been discovered in England. I may mention that the tribe inhabiting the country on the north side of the harbour, where the Cardinal's Palace now stands, was supposed by the tribes from a long way round, to contain men of great shrewdness and cunning; so much so that they tried to get their tribal doctors and rainmakers from there.

So perhaps it was a knowledge of this that induced Phillip to visit them and have a talk. With a boat's crew, including marines, he visited them. The blacks were drawn up in one line, and the white men in another. The Governor commenced to address them by signs and words — perhaps by an imperfect interpreter — when suddenly Woollooraming, a young black, threw a spear at him, and it went into his breast just above the collarbone. Then the whites presented to fire, and the blacks raised their spears, when, with a shout, another young man named Binnalong rushed between them, crying out, as he held his arms stretched to the utmost — 'Bail fire! Bail spear!' He then made the whites understand that it was some movement of the Governor that had caused Woollooraming to spear him. This noble action no doubt saved many lives — the action of a mere boy of about eighteen years.

Phillip, who was not much hurt, was struck so much with admiration of the deed that he named the locality Manly Beach. And I think it was one of the noblest acts which history records of any savage in any clime. So much then for the good fame of my ruined and much maligned black brothers. Nearly twenty years ago there was a movement on foot to change the name of the place to New Brighton, but I protested with all the vigour I was master of against any change of the name which recorded such quickness, courage, and devotion in a young savage.

My letter appeared in one of the Sydney daily papers, and I heard no more of the subject. So much was I impressed with the occurrence that I have for years been trying to induce artists to make a great historical picture of the event for the Art Gallery. The dress and forms of the whites can easily be got, and the best copies of the blacks can be found in 'Major Mitchell's Explorations,' in which full justice is done to the heads of Mozengully, Barnimanwoonga, and others. But what a change hath the mighty, mighty dollar wrought! All sentiment sinks before it; it is the Dazon of the day, and its worshippers are many.

Boomerang

Legacy

Citation details

F. D. McCarthy, 'Bungaree (c. 1775–1830)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bungaree-1848/text2141, published first in hardcopy 1966, accessed online 13 February 2025.

This article was published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, (Melbourne University Press), 1966

The Australian Museum

The National Museum

Select Bibliography

T. Welsby, Bribie the Basket Maker (Brisb, 1937).